William Harris

This man deserves a longer article, but I couldn’t resist this clipping from the London Standard, via the Montreal Gazette, 3 May 1912.

THE SAUSAGE KING.

Mr William Harris, who has been known during the last 25 years as “The Sausage King,” died yesterday at his establishment at the corner of St John street, Smithfield, E.C. He had been confined to his bed for only three days, and death was due to heart failure caused by bronchitis.

Mr Harris, who was 69 years of age, worked a butcher’s round in Woolwich and Greenwich as a boy, and he started his career in the sausage business with a stall in Old Newgate Market. About forty years ago he took the ship at St John street, and he has lived in the flat above ever since. By dint of hard work, and, more particularly, clever advertising, he built up a new business, and was one of the most famous caterers in Victorian London. At one time he had forty shops in various parts of London, and others in Southend, Brighton, Portsmouth, and other centres. As the leases of the shops expired, however, he gave them up and devoted his energies entirely to the wholesale sausage trade, supplying the army and navy and large firms. There are now only about half a dozen of his shops in London.

The “Sausage King” was somewhat eccentric, but this was to a large extent due to his love of “personal advertising,” which was his motto for business success. At all times of the day he wore a sort of evening dress, with an opera hat, and a blazing diamond in his white shirt, even when buying in the market, and he used not a scrap of writing or wrapping paper that did not bear his photograph. His trade mark, which he registered about forty years ago, depicts him winning the “Pork Sausage Derby” on a fat porker. His principal catch-phrase was “Harris’s sausages are the best,” and it spread the fame of his sausages all over the world. He also composed a lot of poetic advertisements, which caused much amusement.

At first Mr Harris used to sell his sausages to the butchers who had stalls in the market, and he was noted for his eccentricity even then. He was anxious to know whether the customers preferred the sausages containing chopped sage or those without it. He was seen, as he sold each sort of sausage, putting a pea into one or other of his coat pockets in order to record their respective popularity.

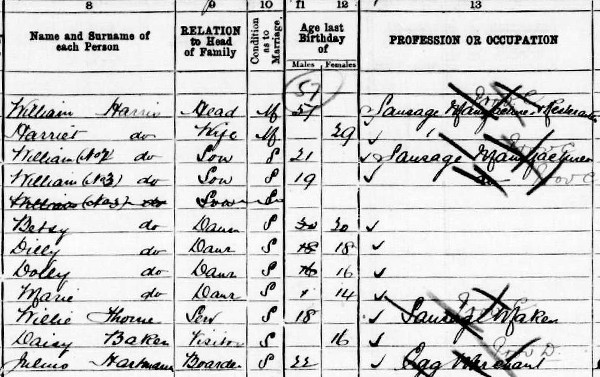

Another of his eccentricities was to name each of his three sons William and his four daughters Elizabeth. To this day his three sons are known as “Number One,” “Number Two,” and “Number Three.” In 1887 he was summoned for not sending “his son William” to school. He promptly brought all three before the magistrate and asked which one was meant. The School Board officer was puzzled, but it transpired that it was the eldest whose education was being neglected. The father explained that he was teaching his sons the business, and he thought that it would be of more use to them than going to school. He was fined 2s. 6d., but he reckoned that the advertisement he obtained was worth quite £20,000. That this figure was not over-estimated may be judged from the fact that columns were devoted to the case, and he was caricatured in all the humorous papers.

Every Christmas Mr Harris sent a gift of 1 lb. of sausages to each policeman and fireman in the City of London and in all other districts where he had a shop. About 15 years ago, when sun-bonnets for horses were first introduced, the “Sausage King” drove a mule from Folkestone to London with a parasol fixed over the animal’s head. All the brown and white Shetland ponies which drew his red advertisement carts around the streets of London two years ago were bred by himself in his own stables in the city.

Pearce edited a short-lived newspaper for Harris, called Marrow Bones and Cleavers.